Flying a Rockwell Commander Taught Me to Ship Better Code

Explore my tools: agents-skills-plugins

The Commander and the Compiler

There's a moment during pre-flight when I'm standing under the wing of my Rockwell Commander 112, checking fuel sumps for water contamination, and I think about code review.

Not because I'm obsessed with work. Because the processes are identical.

You're methodically checking every critical system before committing to an irreversible action. In aviation, that action is taking off. In software, it's deploying to production. Both domains punish you severely for skipping steps.

The Commander is a 1970s-era single-engine aircraft that Rockwell designed to compete with the Piper Cherokee and Cessna 182. It's got a distinctive look - low wing, swept tail, almost aggressive stance on the tarmac. When I bought mine, a more experienced pilot told me: "The Commander rewards pilots who follow procedures and punishes those who don't."

He could have been talking about TypeScript.

Checklists Are Just Code Review for Meat Computers

Every flight starts the same way. I pull out the laminated checklist and work through it systematically. Fuel quantity - check. Oil level - check. Control surfaces - check. It's boring. It's repetitive. It's the reason I'm still alive.

// Pre-flight checklist as code

interface PreFlightCheck {

fuelQuantity: number;

oilLevel: 'adequate' | 'low' | 'critical';

controlSurfaces: 'free' | 'restricted';

weatherBriefing: boolean;

notams: boolean;

}

function canTakeoff(checks: PreFlightCheck): boolean {

// No shortcuts. Every condition must pass.

return (

checks.fuelQuantity > MINIMUM_FUEL_REQUIRED &&

checks.oilLevel === 'adequate' &&

checks.controlSurfaces === 'free' &&

checks.weatherBriefing === true &&

checks.notams === true

);

}

// There's no "skip checks" flag in aviation.

// There shouldn't be one in your CI pipeline either.

I've worked with developers who treat code review like a speed bump - something to route around when they're in a hurry. I used to be one of them. Flying changed that.

When you're at 8,000 feet and the engine starts running rough, you really wish Past You had been more thorough during pre-flight. When you're debugging a production incident at 2am, you really wish Past You had caught that edge case during review.

The Accident Chain

In aviation, we talk about the accident chain - the series of small decisions and oversights that link together to cause a crash. No single link is catastrophic. But chain enough of them together, and you're in trouble.

- Skipped the weather briefing (just a short flight)

- Didn't check NOTAMs (probably nothing important)

- Fuel was "probably fine" (didn't want to delay)

- Ignored that slight engine roughness during run-up (it'll clear up)

Each decision seems reasonable in isolation. Together, they kill pilots.

Software has the same pattern:

- Skipped the unit test (it's a small change)

- Didn't update the documentation (who reads that anyway)

- Merged without code review (it's Friday, I want to go home)

- Ignored that flaky test (it usually passes)

I've seen production outages at Chainbytes that traced back to exactly this pattern. Bitcoin ATM software doesn't forgive sloppy processes any more than a Lycoming engine does.

What the Commander Teaches About Systems Thinking

The Commander 112 is a systems aircraft in a way that simpler trainers aren't. It has a constant-speed propeller, retractable gear, and enough electrical systems to keep you honest. Learning to fly it means learning to think in systems.

When something goes wrong, you can't just panic. You run the checklist:

- What's the actual symptom? (Not what you assume - what you observe)

- What systems could cause this?

- What's the immediate action?

- What's the longer-term fix?

Sound familiar? It should. It's the same debugging process I use for code.

That systematic thinking has made me better at building agentic tools. When I'm designing a skill or debugging a plugin, I think about failure modes the way I think about engine-out procedures. What can go wrong? What's the recovery path? What does the user see when things fail?

The Joy of Competence

There's a specific kind of satisfaction that comes from doing something difficult, well. Landing the Commander in a crosswind, keeping the upwind wing low, touching down on one main gear and letting the other settle - that feeling of earned competence is hard to replicate.

Writing software that works - really works, handles edge cases, fails gracefully, does what users actually need - gives me the same feeling.

Both require practice. Both require humility. Both require the willingness to be bad at something for long enough to become good at it.

I spent a lot of hours in that left seat before I felt genuinely comfortable. I've spent even more hours in front of a terminal. The Commander taught me that competence isn't a destination. It's a practice. You maintain it through repetition and reflection, or you lose it.

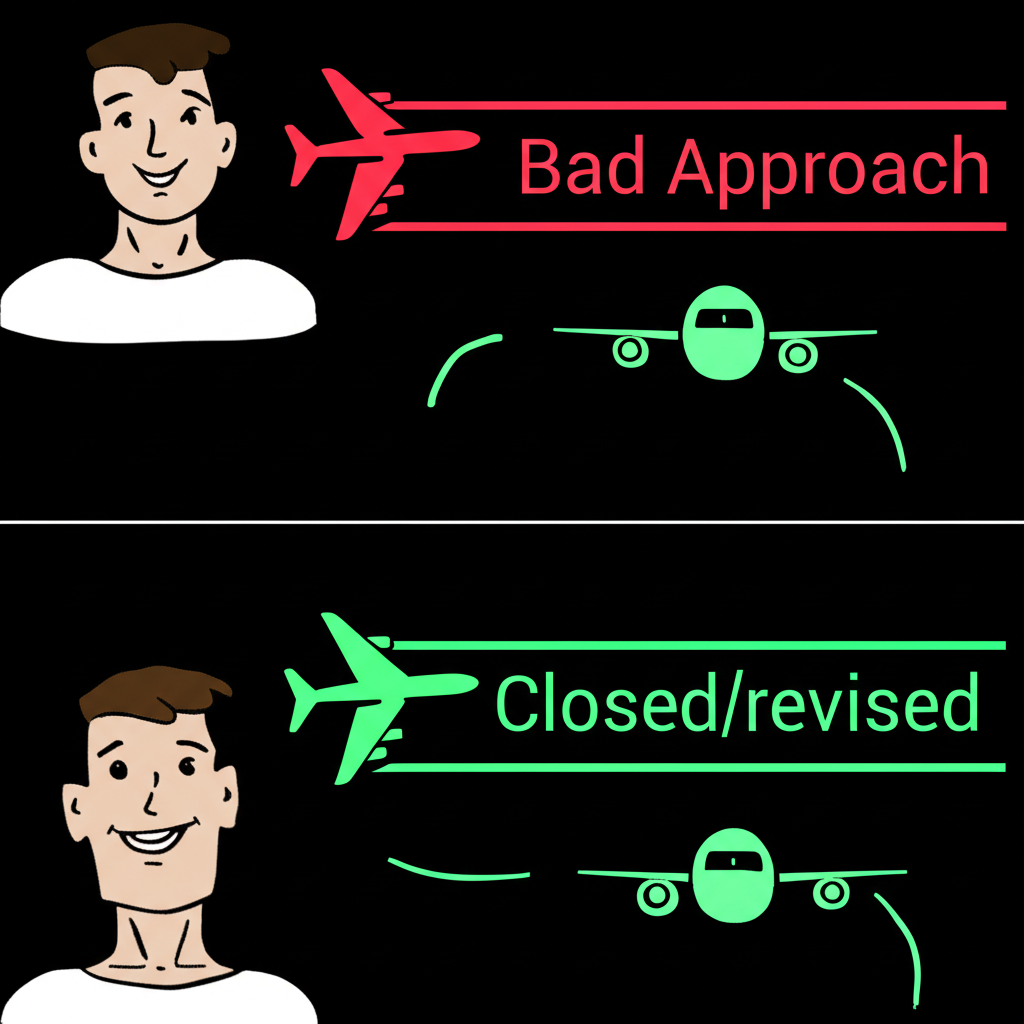

Go-Around Mentality

The most important decision a pilot makes isn't when to land. It's when not to land.

A go-around - adding power, cleaning up the configuration, climbing away from a bad approach - feels like failure. You were so close. Everyone on the ground is watching. Your ego wants you to salvage it.

But unstabilized approaches kill pilots who let their ego make decisions.

In software, the equivalent is knowing when to abandon a PR. When the code review reveals fundamental design problems. When you've been debugging for three hours and you're just making it worse. When the right answer is to close the laptop, go for a walk, and start fresh.

I've shipped bad code because I was too invested to walk away. I've never landed badly because I was too invested - because aviation trained that instinct out of me.

Go around. It's not failure. It's judgment.

The Long Runway

Every flight in the Commander reminds me why I build software the way I do. Not because I think code is literally as dangerous as aviation (it usually isn't). But because the mindset that keeps pilots alive - methodical, humble, systems-oriented - also produces better software.

Checklists aren't bureaucracy. They're respect for complexity.

Testing isn't paranoia. It's acknowledging that you'll miss things.

Review isn't criticism. It's a second pair of eyes on systems that matter.

I'm still learning in both domains. Every flight teaches me something. Every debugging session reveals a gap in my understanding. The Commander is 50 years old and still teaching new pilots. Good codebases do the same.

If you're a developer who's ever thought about learning to fly - do it. Not because it'll make you a better programmer (though it might). Because standing on the ramp after a good flight, oil on your hands, checklist complete, is one of the few feelings that rivals shipping good code.

See you in the pattern.

"Flying is learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss." - Douglas Adams

Clear skies and clean builds.

One reaction per emoji per post.

// newsletter

Get dispatches from the edge

Field notes on AI systems, autonomous tooling, and what breaks when it all gets real.

You will be redirected to Substack to confirm your subscription.